Ranging - Part 5

What is Ranging?

Ranging is a technique useful in all types of boating to determine whether you are sailing a straight course over ground or are being pushed one way or another (by leeway or current). It is also useful to tell you whether your current course will allow you to clear an object (get through the gap in the Berkeley Pier, say).

The basics are described in Part 1, which describes how to use it crossing a channel with current to maintain a straight course across. Part 2 shows ranging to determine whether you can clear an object, Part 3 shows how to use it to determine your position in certain cases. anmd Part 4 uses a variant to tell you whether you are on a collision course with another boat.

This time I will be controversial and show you why a technique sometimes taught at the Club to determine collision courses using a sort of ranging does not work.

What We Learned Last Time

You and another boat are on a steady course. If the bearing to the other boat does not change as it gets closer, you are on a collision cours. Otherwise not. This is how radar works.

Not only that, the Navigataion Rules require that you use this method. I’ll reference Rule 7 – Risk of Collision (Inland)

(c) In determining if risk of collision exists the following considerations shall be among those taken into account:

(d) such risk shall be deemed to exist if the compass bearing of an approaching vessel does not appreciably change; and (ii) such risk may sometimes exist even when an appreciable bearing change is evident, particularly when approaching a very large vessel or a tow or when approaching a vessel at close range.

David Burch is the author of 13 books on marine navigation and weather and the director of Starpath School of Navigation in Seattle, WA. His books include Inland and Coastal Navigation: For Power-driven and Sailing Vessels and Fundamentals of Kayak Navigation. In the latter book, he presents a tecnique for kayaks very similar to what I showed in Part 4. You can see this in one of his blog posts from 2022. Scroll down to Risk of Collision to find it.

What you won’t find in any of David’s books is what I’ll discuss next.

You May Have Heard (or Even Been Taught) This

To determine whether you're on a collision course with another boat, line that boat up with something behind it on land. As you get closer, if that point on land does not move, you are on a collision course. Otherwise you are OK.

I am going to show you why this does not work, except in some trivial cases.

Why This is a Myth and Doesn’t Work

I’ll do two explanations of this, one showing visually how the background lines up with the other boat on a collision course, and the other using what we learned from radar.

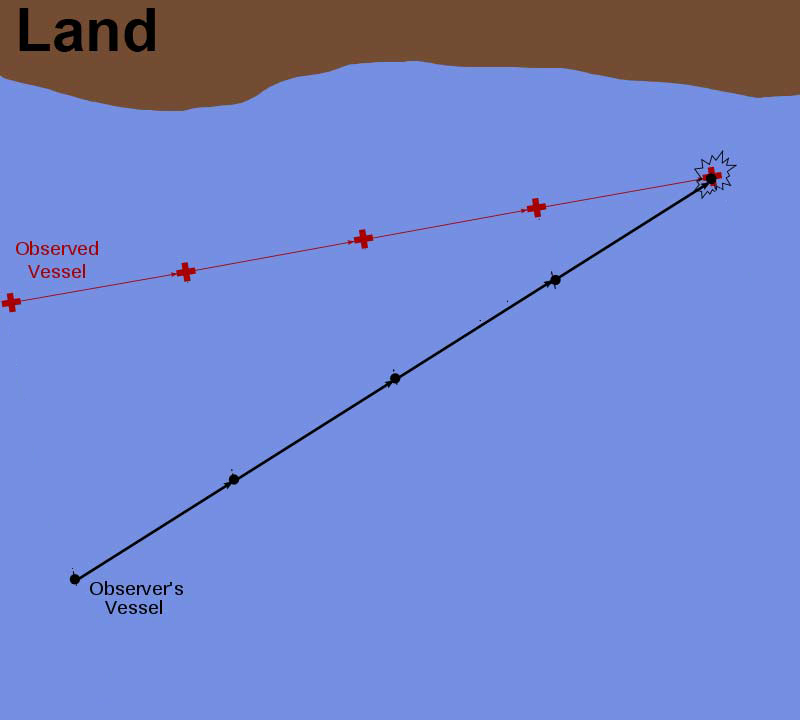

A Typical Collision Course

Here’s a typical collision course:

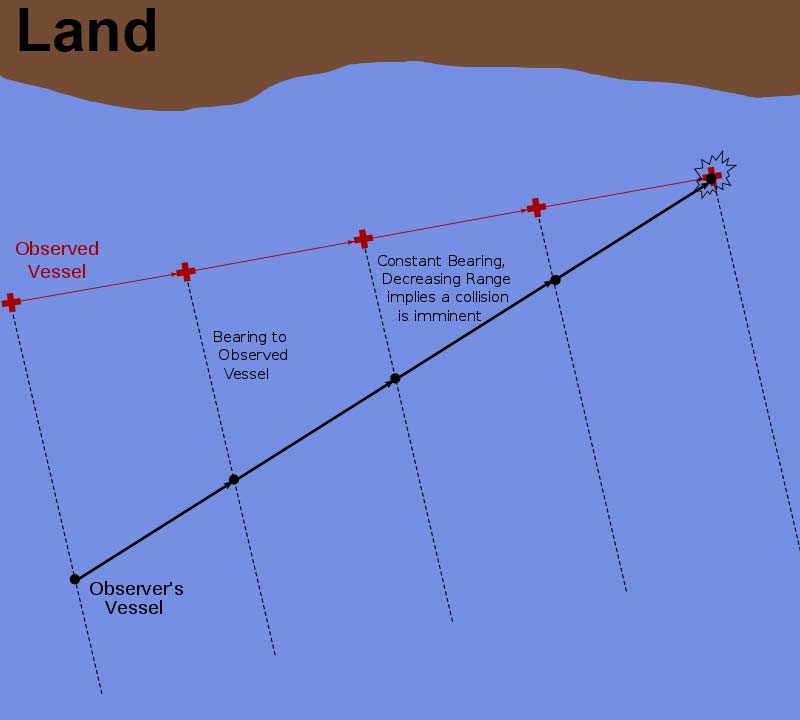

Let’s look at bearings to the observed vessel as we get closer to it:

And we see what we learned from the radar discussion – constant bearing with decreased distance.

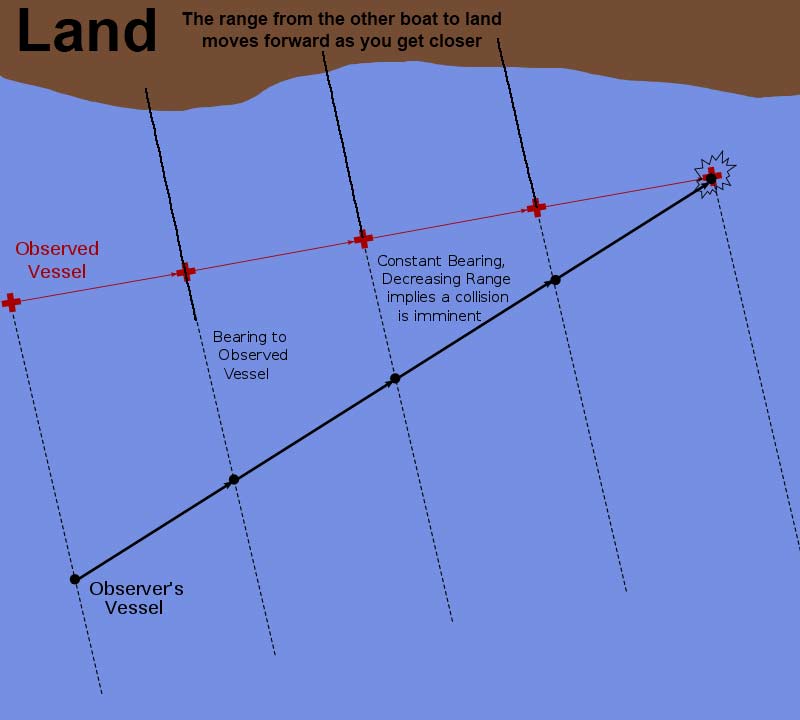

Now let’s look at what’s happening with objects on the land behind the other vessel as we get closer:

They are moving to the right, not staying fixed as the myth would suggest. So it doesn’t work. Pretty clear?

Another Way to See It

You and another boat are on a steady course. If the bearing to the other boat does not change as it gets closer, you are on a collision cours. Otherwise not. This is how radar works. If you do not believe it, do not take a ferry in the fog, as they are using this technique.

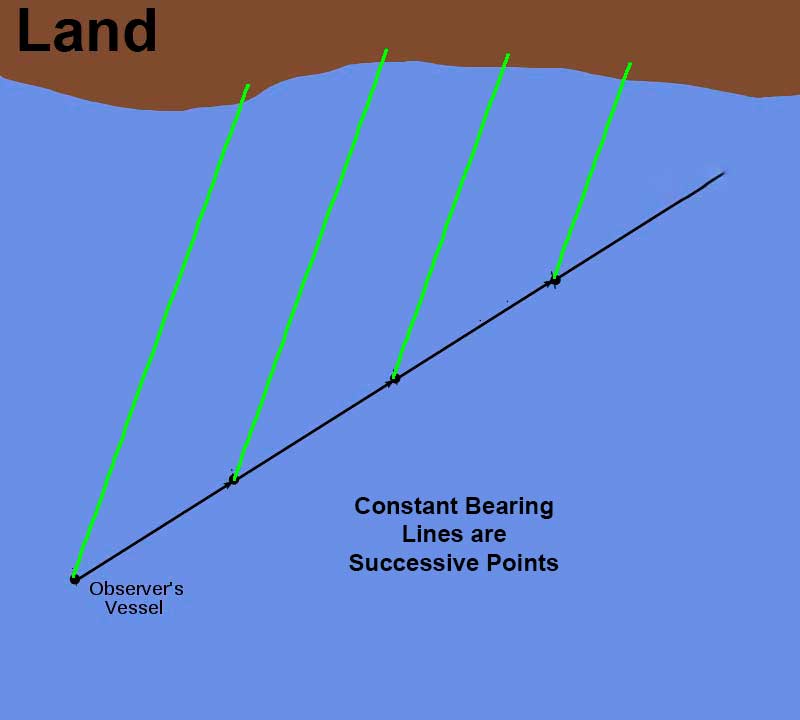

This means that if you’re on a collision course, the bearing to the other boat will be the same as you get closer. Now forget about the other boat, and just think about a constant bearing from your boat to anywhere. Pick one, say 127°, could be anything. Take that bearing to some land in the distance, and look at what happens as you go forward. The point has to move, correct? So the point in land behind the boat you’re on a collision course with has to move. No way around it.

Let me throw one more thing into the mix. If the point on land on the constant bearing line did not move, some long-standing navigation techniques of determining your position using two or three bearings to points on land would not work. You can think about that one.

You Can Test It Yourself

It ain’t hard, and you can do it on land. Set up two people as “boats” walking into a collision course, and look at how the other “boat” lines up against the background as you get closer to a crash.

It Actually Works in a Very Few Uninteresting Cases

For headon collisions and running into someone on exactly the same course, the myth does work. But those cases are uninteresting.

What You’ll Find on the Internet

You'll find that noboby teaches this method (the myth). You’ll find discussions with things like “I’ve used it for years, and then I took a navigation class with a retired Navy captain, and he slapped me down and said it didn’t work”. You’ll also find discussions with things like “I think it works approximately well” with nothing to back it up.

The Annapolis Book of Seamanship makes a brief reference to something similar, but the diagram they supply pretty much shows that it doesn’t work. Go figure.

I’m firmly in the camp that you personally don’t need to be able to explain why something works in sailing in order to teach it(I don’t think that for most people knowing the theory helps that much). But there has to be an explanation somewhere. Or there has to be a demonstration somewhere showing that it works, even if why it works in unclear. Otherwise it’s just folklore. You'll find neither of these for the myth.

David Burch Weighs In

Recall that David is the author of multiple books on maritime navigation whom I mentioned above. I sent him a note about this, and here is his repsonse, which is a different take on why it doesn’t work:

On a collision course it will be true that the compass bearing to the target will remain constant until you crash. And we need a good bearing compass for that—or a steady heading and don't move the eye and watch the vessel relative to the rigging. But a bearing to a landmark behind the target is not useful. If you watch a target during the time you move .5 nmi (ie 5 min at 6 kt) then the horizon target must be 143 nmi away to have the bearing remain the same to within 2º from start to finish. ie simply not doable.

Conclusion

I hope to have presented (in Part 4) a very simple (and simple to understand) method for determining whether you are on a collision course. And I hope to have shown you why this particular method that I’m calling the myth does not work.

It is far from my intention to disparage in any way the very fine sailors at Cal Sailing who have believed in and taught what I have called the myth. But challenging received wisdom in a constructive way is how we collectively advance our knowledge. I hope that I have done that. And I hope all of you challenge what I have said, here and elsewhere, and help me advance my own knowledge along with yours.

This is the last in this series of blogs. I hope it has been useful. The test is whether it adds something useful to your sailing toolbox.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments