You may know Ryan Alder from the dinghy repair clinics that he started with Memo a couple of weeks ago, or because you bought one of his cool CSC T-shirts, hats or sweaters. You may know Ryan from a dinghy lesson, from open house, from a blog post even, or simply because he is one of the familiar faces that is often at the club. It is sometimes brought up that it is not always easy to be a new member of our CSC community: you arrive at the club, you don't know anyone and most of the time, not much about sailing nor how the club works. We all remember those dark days... But some members make a point to recognize newbies and to be encouraging from one week of lessons to the other. When I started sailing at CSC three years ago, Ryan was one of those members. That helped me know when I could consider getting tested for junior. Since then, he became a senior skipper and has helped many others to get at these difficult tests.

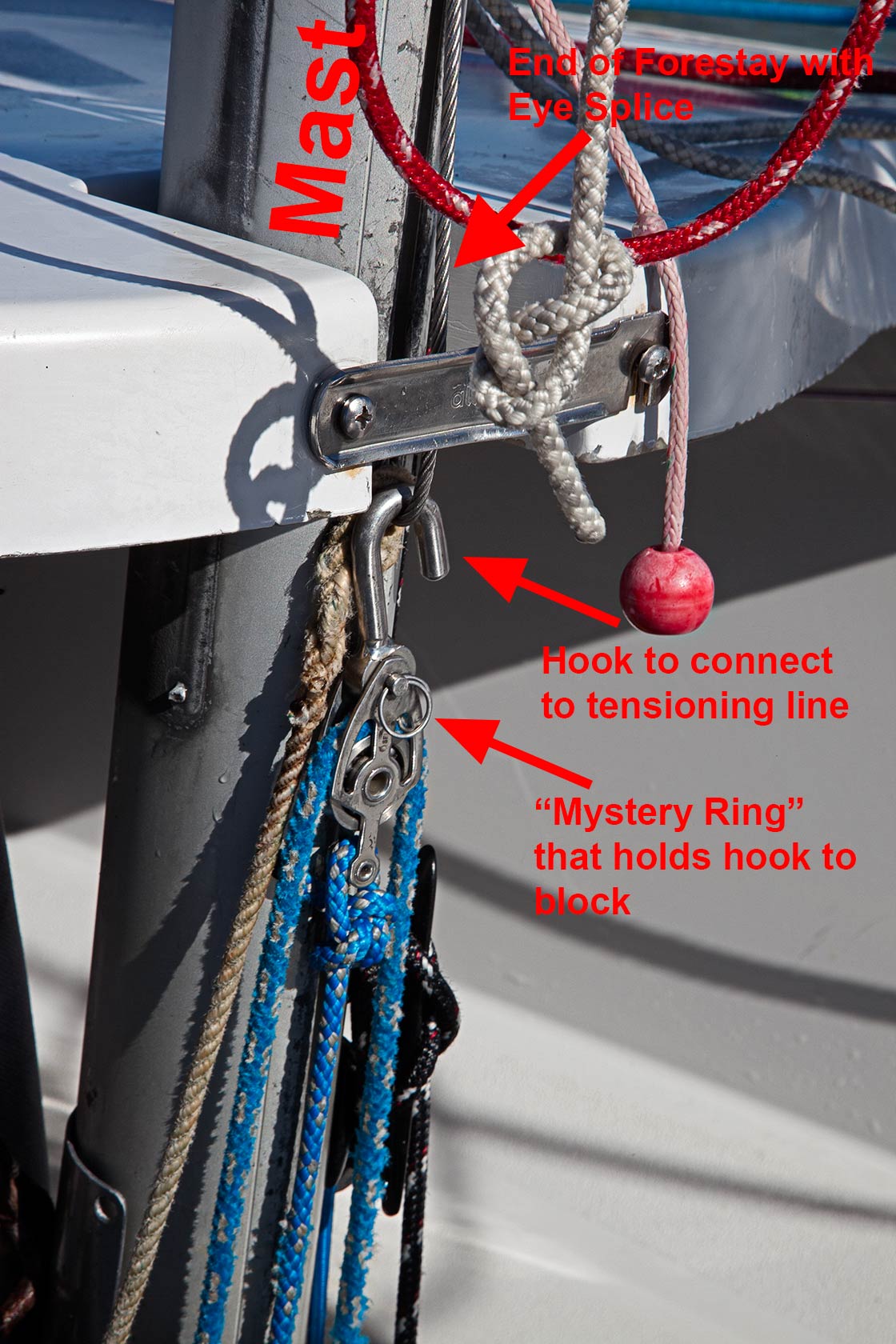

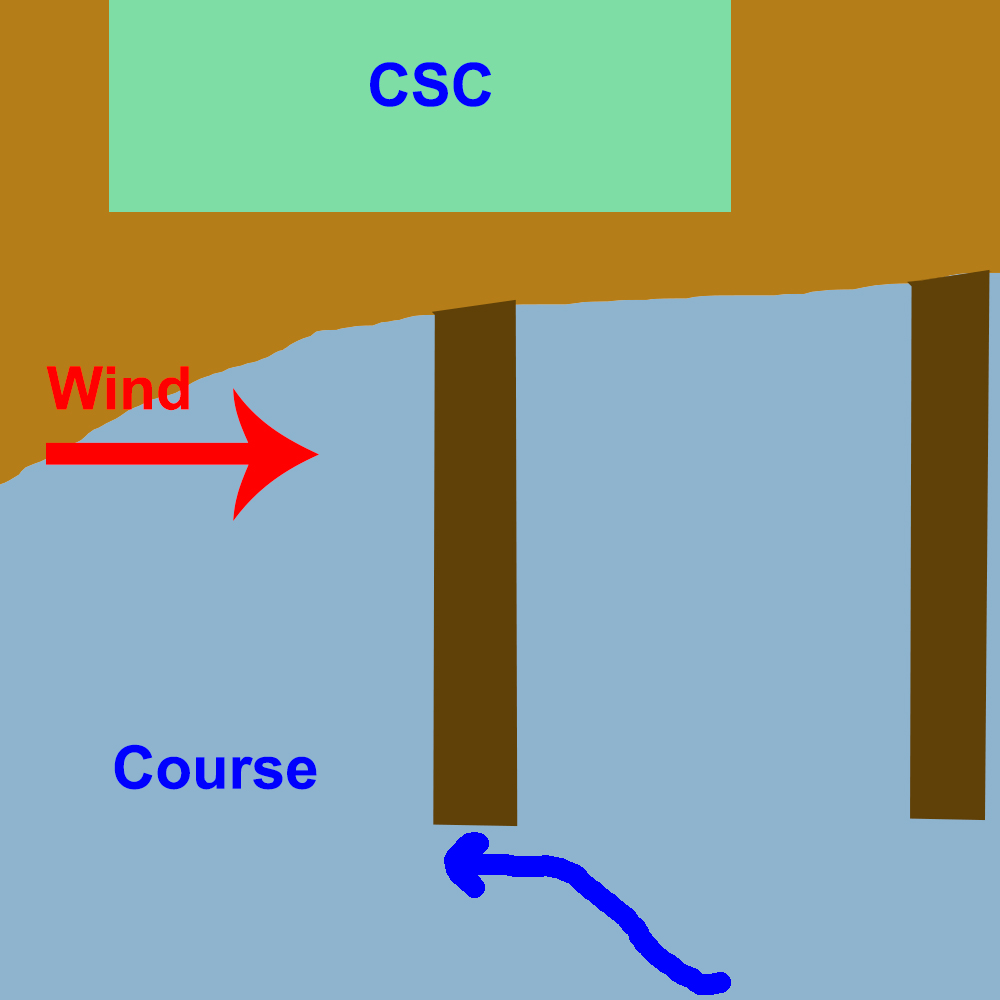

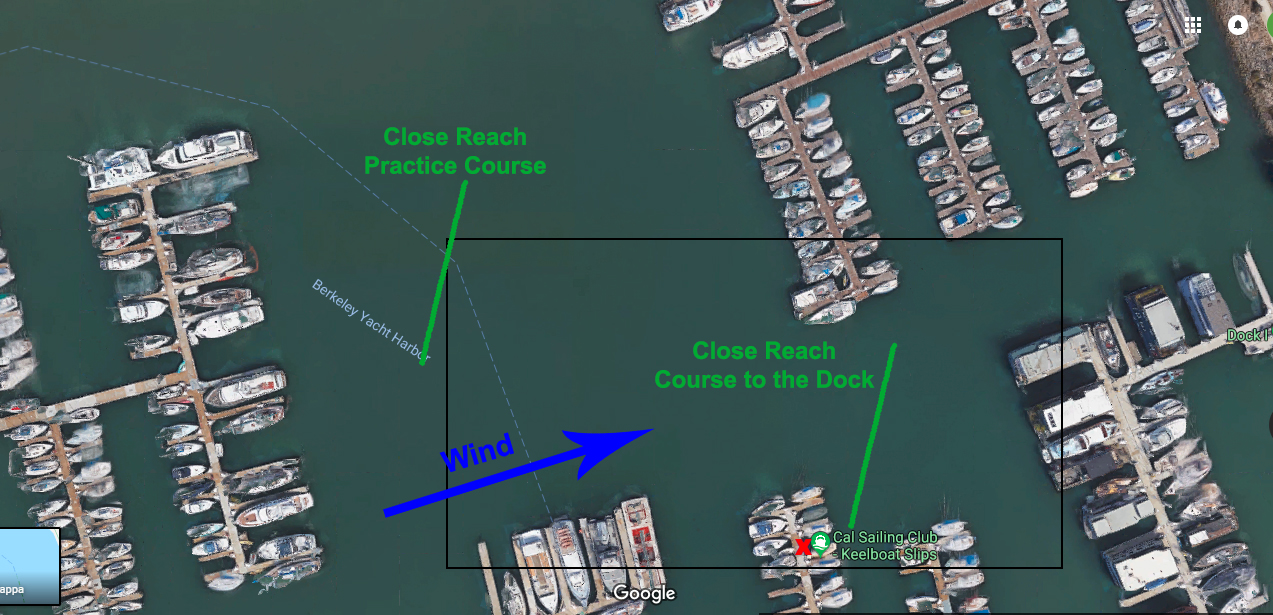

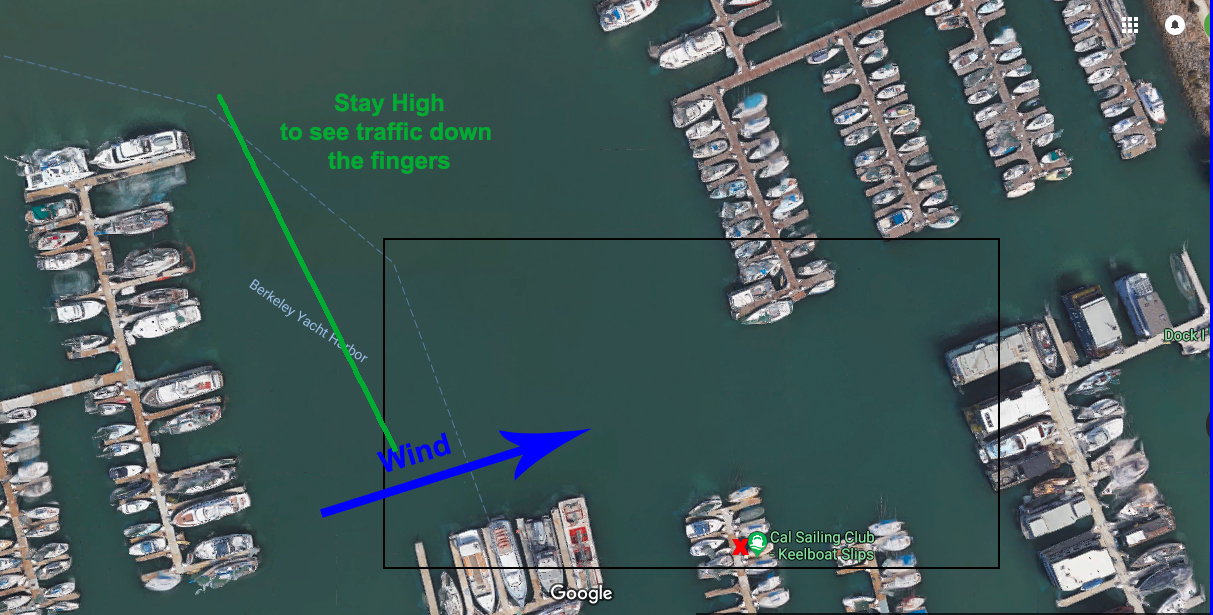

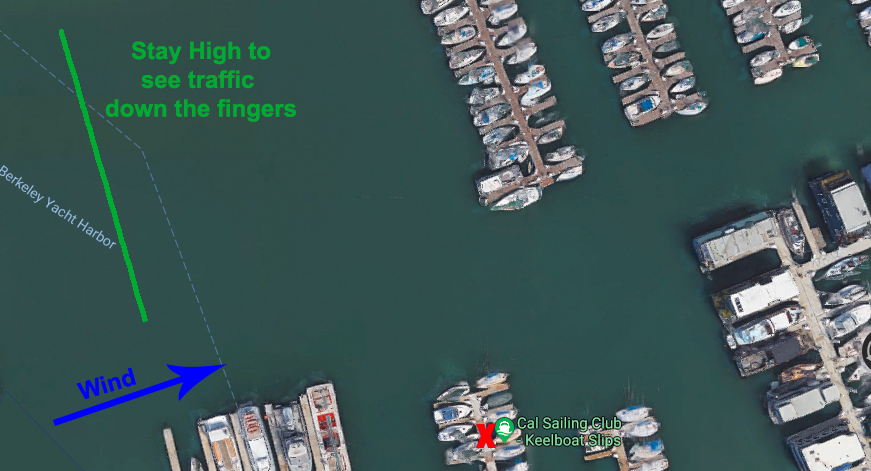

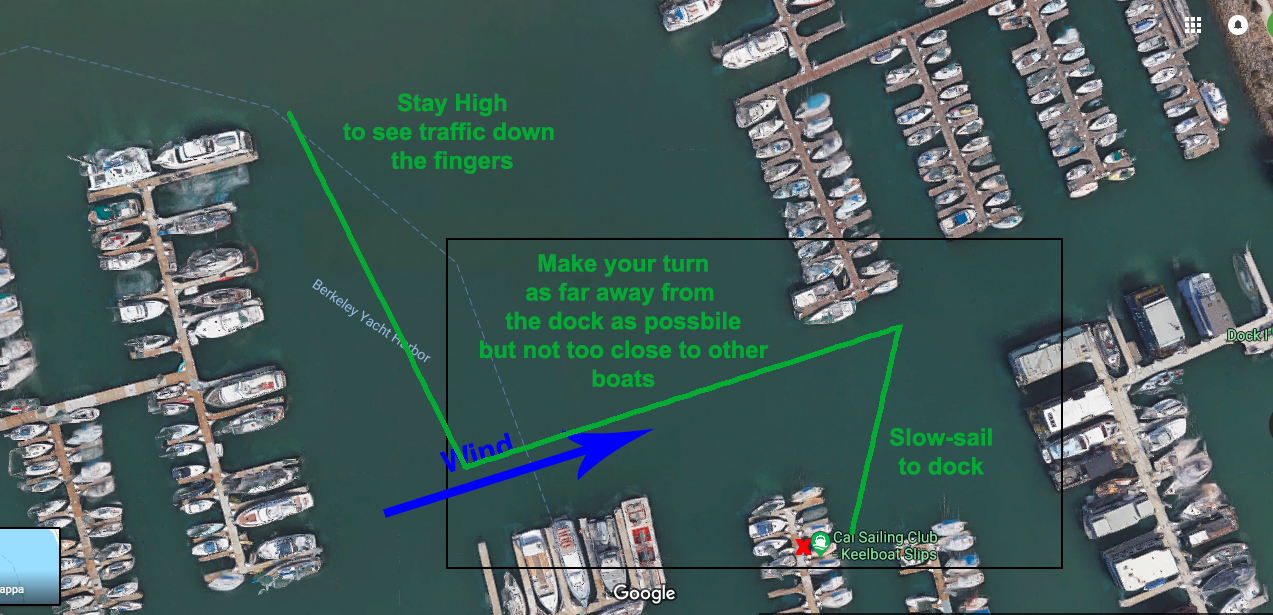

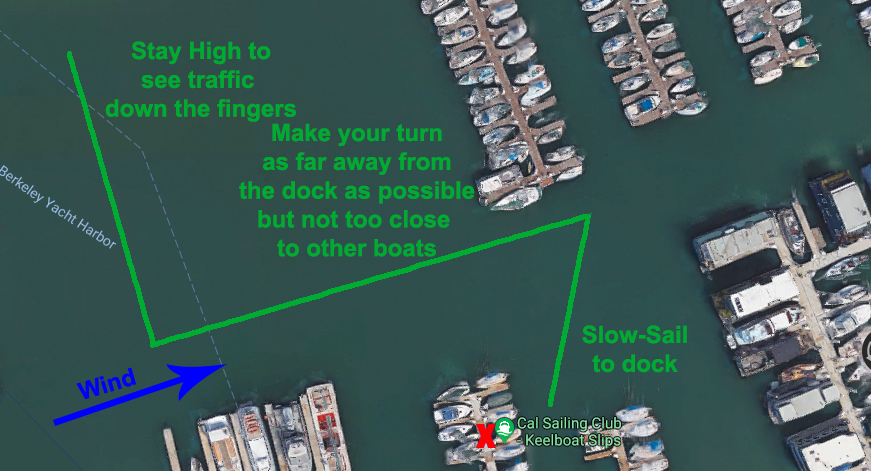

On top of that, Ryan is also Third-Vice Commodore at the club executive committee. This means that in addition to numerous meetings, he is in charge of our fleet of six keelboats, which he recently update with a J80 keelboat, a performant racer that could very well take the club keelboat practice to the next level!

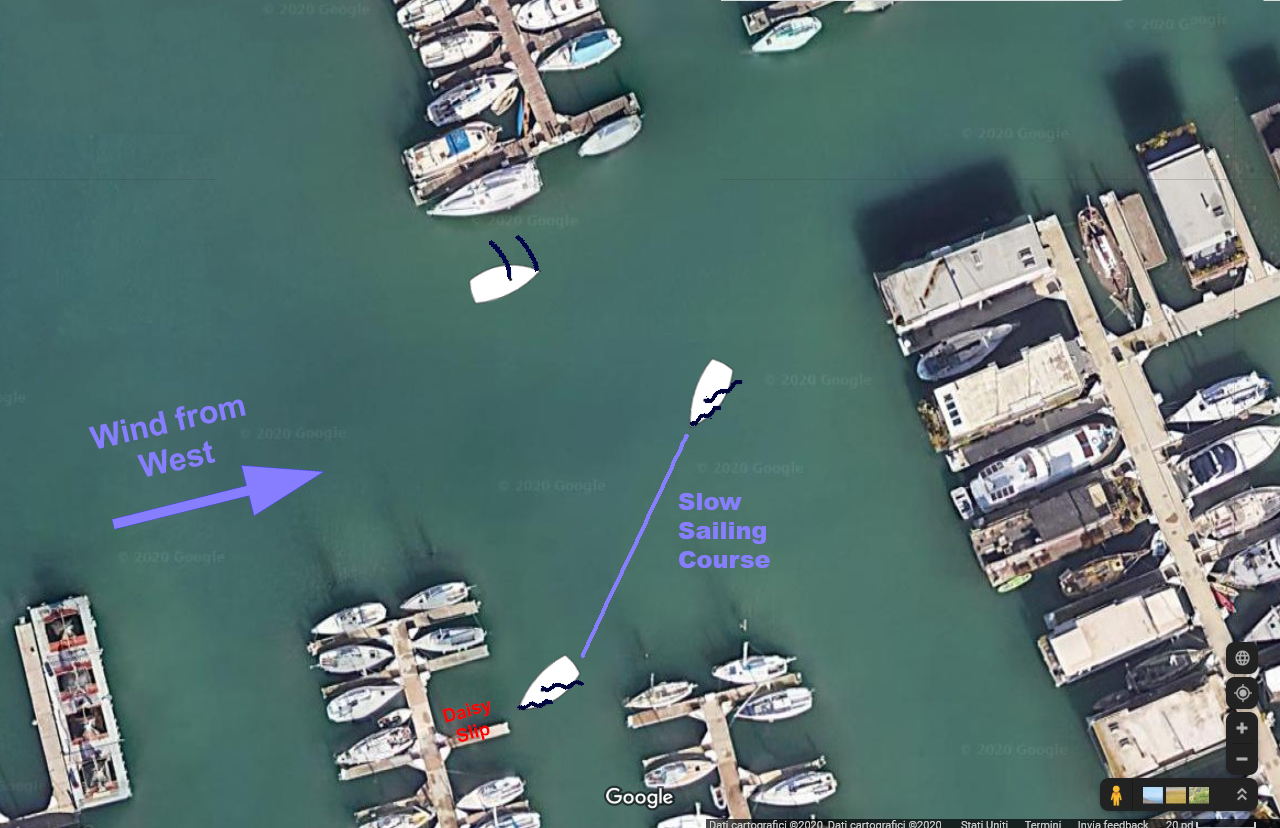

Ryan grew up on motor boats in the Midwest and started sailing CSC six years ago. He now lives on his 30 footer, Kakelekele, in the Berkeley marina. Another excuse to be at (or at least stop by) CSC almost every day!

What made you start sailing?

"Having grown up on/near water I got sick of looking at this beautiful bay and started trying to figure out a way to get out on it and enjoy it. Most options were cost-prohibative until I finally found CSC."

What do you like about sailing in general and the club in particular?

"I fell in love with sailing because it is both a physical and mental challenge, and there is always more to learn. Whatever stage you're at, there is something new to strive towards or improve upon."

"And I love the club because there are so many people that care about and give so much to the club. We make some of the best sailors in the bay, which is one of the most challenging places to sail in the world, and we do it all at virtually no cost to anyone. Because we all share and believe in what we do. I heard tale of someone writing a paper on the club for a sociology or economics class, and the teacher didn't believe them and thought they made it up because 'there's no way that would work in the real world'. But here we are after 50-80 years (depending on who you talk to), still doing it."

What's your best memory at the club?

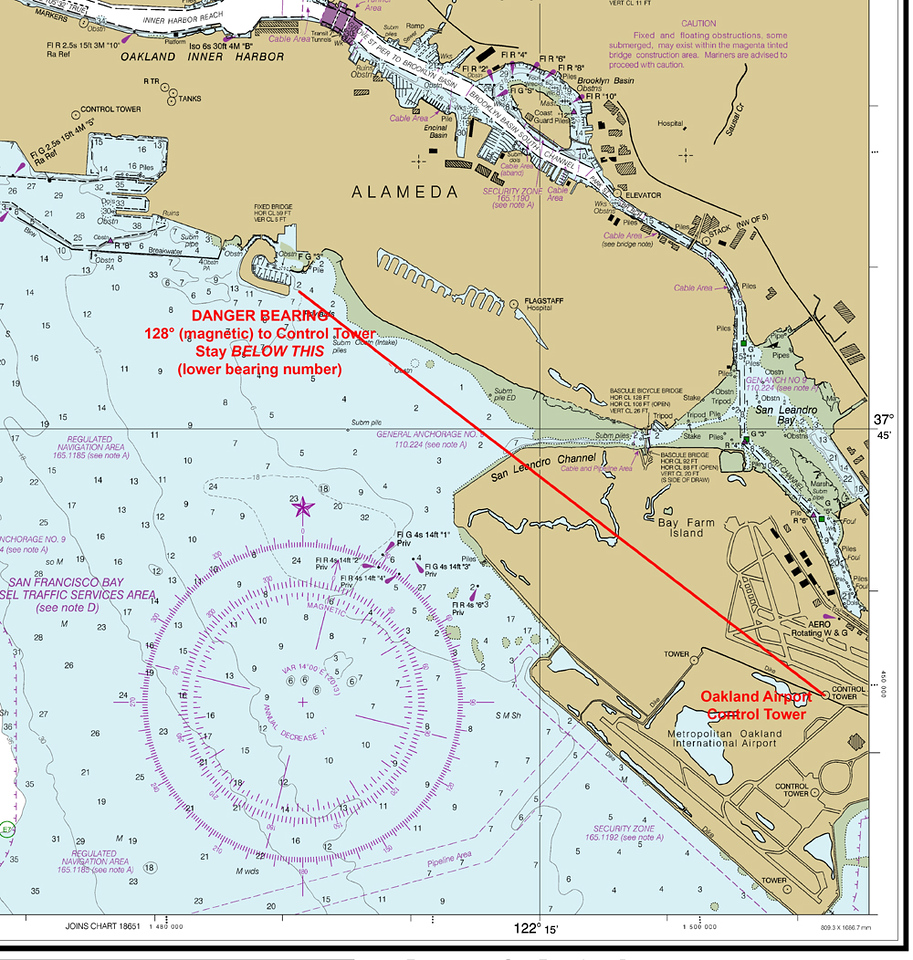

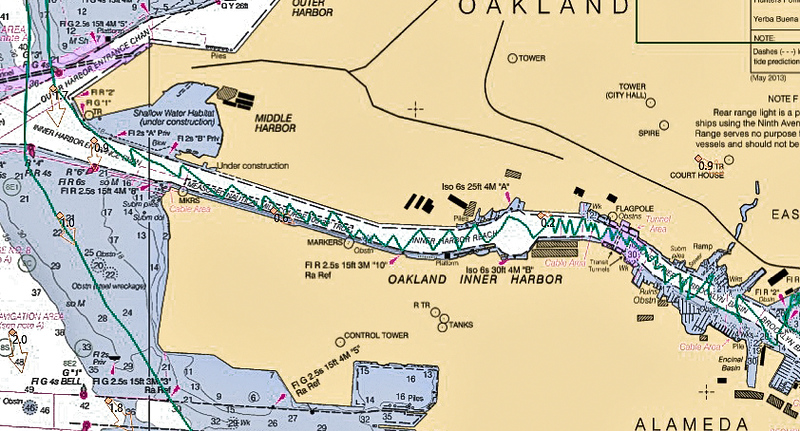

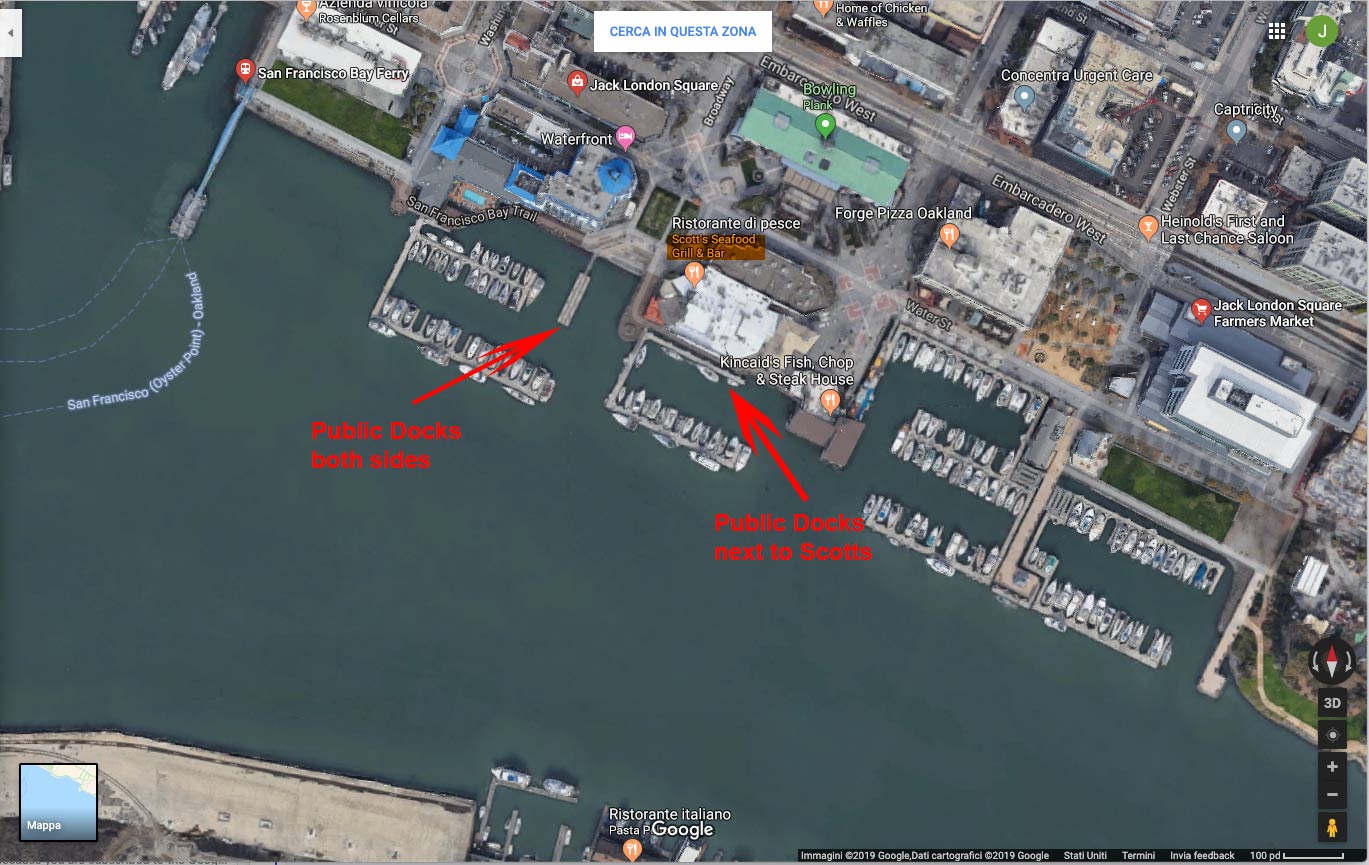

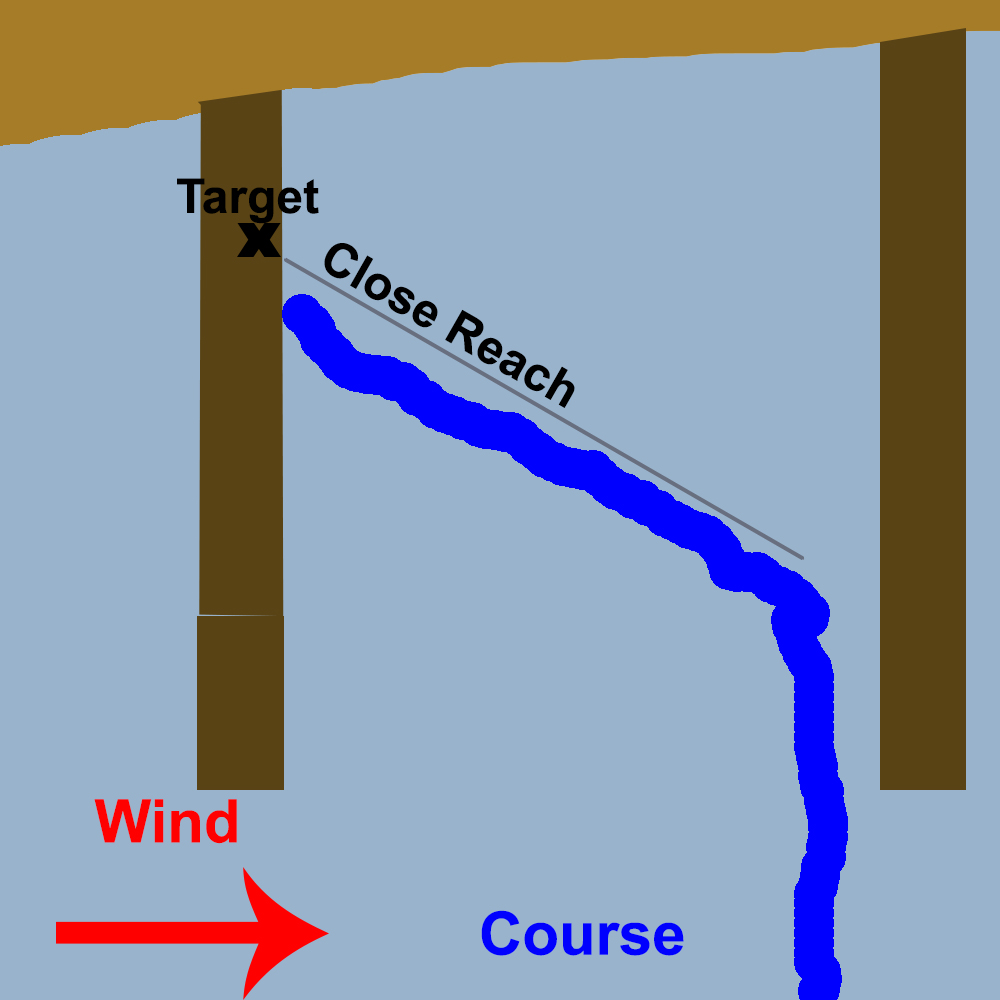

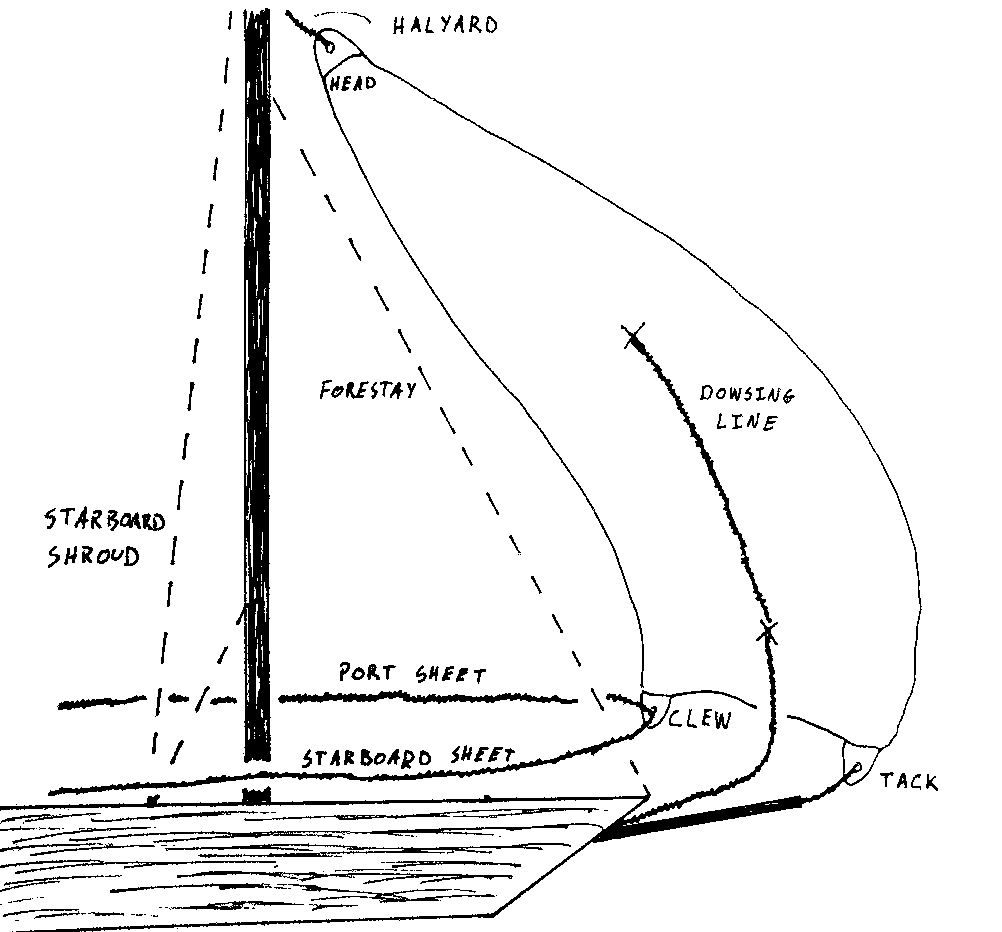

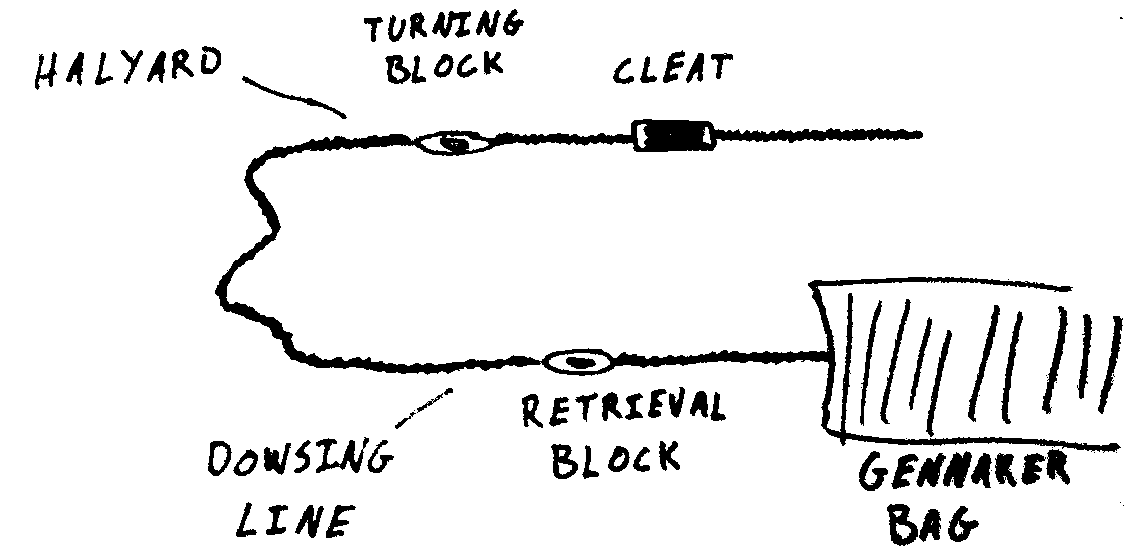

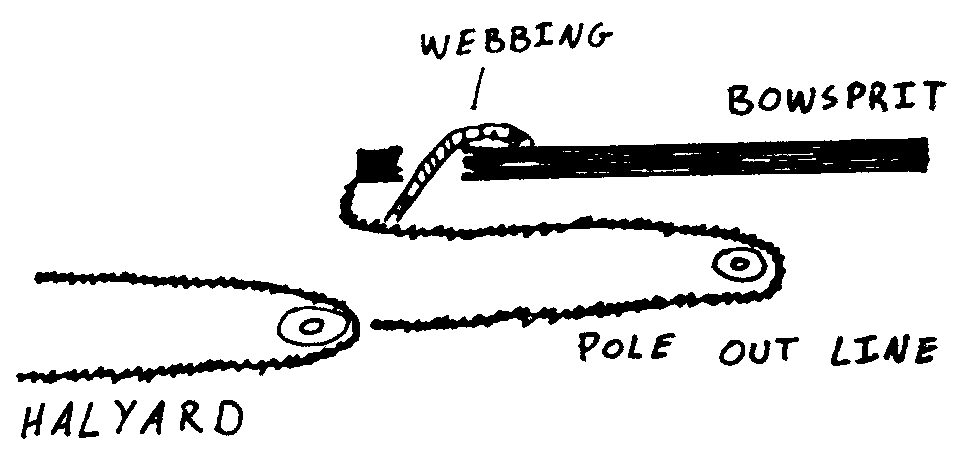

"Hmm this is a hard one, there are so many. The one that stands out right now is from this past summer. James led a dinghy camping cruise to Angel Island, which is a logistical feat in itself, and everyone had a blast. The next day we all made a gate run before heading back. The fog came in pretty thick on the way and there was some discussion on if we were still going to do it. After careful consideration we decided to go for it and make sure to stay in close visual contact. After crossing under the bridge (which we could barely see in the fog) and turning back downwind, we all hoisted the gennekers. Seeing absolutely nothing except fog and all 4 ventures in close proximity flying kites downwind will be one of the most beautiful and awesome experiences I'll ever have."

More about this adventure in

Pan Pan from Seamus.

Any sailing dreams?

"My ultimate dream is to sail the Carribean or the Meditteranean. Good wind, beautiful weather, warm water. Although if I do I'm pretty sure I'll never come back."

What advice/recommendation would you give to a new club member?

"Talk to people. Ask sailing and windsurfing questions. This is, even more than sailing, a social club. Progress gets much easier when you start to get to know some people. Come hang out even if you don't intend to go sailing, especially on a weekend when the clubhouse deck is full of bench sailors. Beyond that: sail, sail, sail. Don't worry about specific skills. It's all about time at the tiller in increasingly challenging conditions. When you start just having fun in higher and higher winds, all the other stuff gets easy."

Could you give us more detail about your role as Third Vice Commodore of our club?

"As 3rd vice I'm in charge of the keelboat fleet. We have a small handful of amazing people that handle most of the maintenance of the boats, namely Greg and Sheldon (and Peter for the motors). So honestly, thanks to them, my role is fairly easy. I mostly manage the keelboat budget and try to make sure they have the resources and support to do what they do best."

Thanks to Ryan and all the CSC volunteers that make our club the way it is, a fantastic place to learn sailing and windsurfing and an amazing community.